China seeks to expand its influence in the Middle East by opening the first consulate in a strategic Iranian trade and military port.

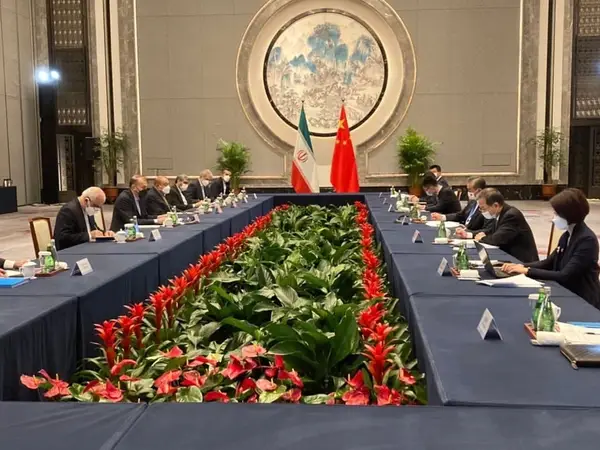

Iran’s Council of Ministers approved the opening of a Chinese consulate in Bandar-Abbas, Iran’s most significant trading and military port on December 29th, 2021—China’s first consulate in Iran. Mohammad Keshavarzzadeh, the Iranian ambassador in Beijing, said “the opening of China’s consulate general in Iran’s southern port city of Bandar-Abbas will greatly contribute to the development of trade between the two countries.”

While at face value this may seem like a benign partnership between two developing countries, it might have far-reaching significance for Iran and the region.

Bandar-Abbas is in the Strait of Hormuz—the slender channel connecting the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman. On the north coast of the Strait of Hormuz lies Bandar-Abbas, and on the south coast, just 55 km across the shore, the Arabian Peninsula. According to The New York Times, twenty percent of all oil shipped globally passes through these waters, making it one of the world’s most strategic chokepoints, as it also has key military, economic, and political importance to the Middle East.

The new Chinese consulate in Bandar-Abbas will share its home with The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps’ main naval base. Iran’s invitation of an emerging global superpower into their backyard could pose a threat to Iran, should regional disputes one day arise.China has already “attempted to claim more internal waters, territorial sea, exclusive economic zone, and continental shelf than it is entitled under international law.” says Commander Reann Mommsen, a spokeswoman for the US Navy’s Seventh Fleet. She describes China’s territorial claims as “excessive,” regarding the Paracel Islands, which are claimed by Taiwan and Vietnam.

In addition to opening the new consulate, according to a recently leaked 25-year ‘Cooperation Program’ between China and Iran—both countries under economic sanctions by the United States and the western world—China is investing in Iran’s cybersecurity, infrastructure, and energy sectors.

According to DW News, “China, the world'slargest public lender to developing countries, imposes unique conditions on borrowing nations which could be giving Beijing undue influence over their economic and foreign policies, according to a study from Germany's Kiel Institute for the World Economy (IfW).”

Mohammad-Hossein Malaek, former Iranian ambassador to China, told the Iranian Labor News Agency that Beijing is anticipating a leading role in developing the Makran region, the Southern coastal strip of Sistan-Baluchistan province, in Iran. Makran lies to the East of Bandar-Abbas. The move would create a clear geographical link from infrastructure developments China has made to gain regional influence in the South China Sea and would allow said influence deeper into the heart of the Middle East.

Beijing has already achieved an agreement with Pakistan to invest billions of dollars over the next 40 years to develop the Gwadar Port. When taken together, developing both this geographical point in Pakistan and the one in Bandar-Abbas creates a “trade and energy corridor stretching from the Persian Gulf, across Pakistan, into western Xinjiang.”

The move comes as China is competing with India for influence in the region, as both nations make efforts to become eminent world powers. India has made similar investments in Iran’s Chabahar port. Unlike China, however, India does not have a global strategy like China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The BRI, originally named, “One Belt, One Road,” is an international development strategy adopted by the Chinese government as China looks to expand its influence worldwide by improving trade routes. As of December 2021, China has expanded its’ BRI—which includes infrastructure developments across land corridors, in ports, across maritime routes, as well as over-land links (bridges, tunnels, etc.)—into 142 countries.Developing diplomatic relations with Iran is crucial to China’s ability to implement the BRI.

“Some believe China engages in ‘debt-trap diplomacy’ through the BRI, ensnaring developing countries with debt dependence and then translating that dependence into geopolitical influence,” says Paul Haenle, former U.S. government adviser and director at the Carnegie-Tsinghua Center, a joint U.S.-China research center based in Beijing.

To vividly illustrate what that looks like in practice, Haenle explains, “China acquired 99 years of operating rights for the Hambantota Port in southern Sri Lanka after costs for the project spiraled out of control, forcing the leaders in Colombo [Sri Lanka’s capital] to give up control of the port in return for a Chinese bailout.”

Despite Yi’s claims, the Cooperation Program comes hot off the heels of the US leaving a power vacuum in the Middle East after its withdrawal from Afghanistan, and an open shift in focus to the Asia-Pacific. The alliance between the US’ biggest economic rival, China, and their biggest antagonist in the Middle East, Iran, further weakens US’ foothold in the Middle East and undermines The United States’ interests in the region.

The 25-year Iran-China Cooperation Program comes at a time when US-Iran tensions are high, and relations strained. Following the United States’ killing of Quds Forces Commander, Qasem Soleimani, the Supreme Leader of Iran, Ayatollah Khamenei, vowed to deal America a “reciprocal blow.” Iran’s cooperation with China could well be a reaction to its bad relations with the US and not a calculated strategic move on Teheran’s part. Nevertheless, China’s foreign minister, Wang Yi says, “the China-Iran Cooperation Program does not target any country.”

Despite ‘maximum pressure’ sanctions introduced against Iran in 2018 by the US, Iran’s value of non-oil trade exchanges with China stood over $19 billion between March 2020 and March 2021. China is currently Iran’s top trading partner. However, out of the two, China alone has enjoyed a favorable trade partnership, while Iran has been isolated internationally by essentially only being able to trade with China, forcing Iran to trade its oil reserves at much lower prices than it would otherwise like, although no official figures are available.

To make matters worse for Iran, Beijing maintains good political and economic relationships with Saudi Arabia, Iran’s primary regional adversary. China is also Saudi Arabia’s top economic trading partner, and the biggest importer of Saudi oil. Unlike Saudi Arabia, however, China pays Iran below fair market rates per barrel, while the Saudis are given fair market prices. US intelligence officials have seen evidence of “multiple large-scale transfers” of sensitive ballistic missile technology being shipped from China to Saudi Arabia. Saudi Arabia is benefiting from having bilateral relations with the US and China, while Iran is getting raked over the coals by China alone, which is also enabling the military capabilities of Iran’s biggest regional rival.

The only shipments currently taking place between China and Iran are oil deliveries, from Iran to China, made at Iran’s expense—the compensation for which is being held as frozen assets by China (some estimate this is up to $20B). The only way Iran can get their undervalued payment for the oil is by purchasing Chinese goods and services. Additionally, any goods and services related to China’s BRI used or provided within Iran are required to use Chinese companies and labor, thus precluding Iran’s own people and companies’ ability to make any economic gain whatsoever during the BRI’s implementation.

A large majority of the 142 BRI partners are low- to middle-income developing countries. Poor nations make up 48% of the BRI partners, and high-income partners make up only 23%.

Although it is hard to say how China will enforce future cases of defaults on debt, the ‘maximum pressure’ sanctions currently in effect against Iran make it more likely they might default on a Chinese loan. Based on what China has done in Sri Lanka, it is not unreasonable that China would similarly try to take control of Bandar-Abbas, should Iran fall short on its’ loan obligations. If Iran had stronger diplomatic relationships with the West, it could keep China in check. However, Beijing’s critics argue China might swap debt for resources or diplomatic rights and/or obligations at later dates. The Middle East is home to several unstable governments, isolated by the West, and desperately in need of foreign investment, but at what cost?