Venezuela Today, Iran Tomorrow? Leeway To Sell Oil

Is a United States decision to ease oil sanctions on Venezuela a precedent for dealing with Iran? Or does it reduce pressure to get more Iranian oil to market?

Is a United States decision to ease oil sanctions on Venezuela a precedent for dealing with Iran? Or does it reduce pressure to get more Iranian oil to market?

A move by administration of President Joe Biden to allow Chevron, the second biggest US oil company, to export Venezuelan oil followed talks beginning Saturday in Mexico between the government of President Nicolas Maduro and the opposition. Revenues currently frozen abroad will be ringfenced by the United Nations into ‘humanitarian spending.’

Battling high inflation, alongside food and medicine shortages, the Venezuelan government has said the “kidnapped” fund would go into helping stabilize the electric grid, improve education infrastructure, and improve the response to this year’s flooding. The UN will manage a fund for over $3 billion currently held by US and European banks fearful of punitive US measures.

But the decision has been criticized on several grounds. The Boston Herald in an editorial November 28 mocked Biden’s interest in “climate-destroying fossil fuels,” suggesting he was offering the Venezuelan government “a political reward” while appeasing US “eco-progressives” over US shale production, slowing as the release of US emergency reserves eases, while the December 5 deadline for tighter Russia sanctions looms.

An investigation by the Reuters news agency, in a feature published Wednesday, highlighted close links between Venezuela and Iran in cooperating to evade Washington’s eagle eye on oil transports. Reuters reported super-tanker Young Yong disguising Venezuelan oil as Malaysian oil. The vessel belongs to a company owned by a Ukrainian national also sanctioned, and is one of three tankers designated November 3 by the US for forging documents to ship Tehran’s oil and so evade US sanctions on Iran.

Gaining an economic windfall

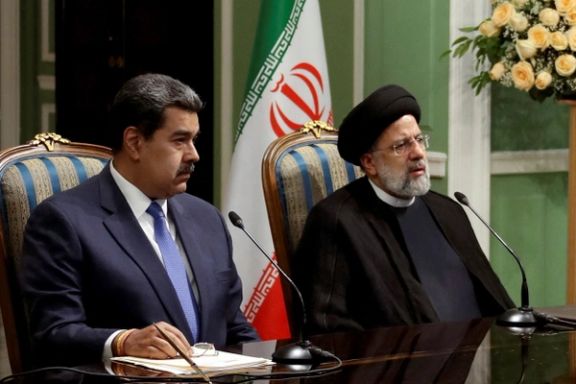

Links between Caracas and Tehran partly explain those arguing against relaxing US pressure on Maduro government and that a double standard is at play. Eddy Acevedo, an advisor at the Wilson Centre, has argued that “both rogue regimes are looking to extract concessions in hopes of gaining an economic windfall.”

Iran and Venezuela in June signed a 20-year cooperation agreement, three years after President Donald Trump in 2019 ramped up sanctions against Venezuela after Maduro won the disputed 2018 election and four years after Trump launched ‘maximum pressure’ against Iran as he withdrew the US from the 2015 Iran nuclear agreement.

The Reuters report suggested Iran had “pioneered” the use of false documents to conceal the origins of cargoes. According to the news agency, around 200 tankers, including 82 super-tankers able to carry up to 2 million barrels, have been involved in servicing both Venezuela and Iran, with the south American country exporting over 360 million barrels in the face on US sanctions since 2019.

‘Smart’ sanctions?

Documentation in the Young Yong case were supplied to Reuters by advocacy group United Against Nuclear Iran, which has since 2013 tracked Iran’s oil traffic to “disrupt…[its] attempts to generate profits from oil sales and further isolate the regime economically.”

So, what are the implications of the Venezuela decision for US Iran policy, when Biden still aims to reach diplomatic agreement to revive the 2015 nuclear agreement? Some analysts in Tehran have argued that Europe’s need for energy in the wake of sanctions against Russia, coupled with upward pressure on US gasoline prices, increased the likelihood of Washington meeting the Iranian demands of ‘guarantees’ that have reportedly stymied talks to revive the 2015 agreement, the JCPOA (Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action).

A decision to replace blanket sanctions on Venezuela with ‘smarter’ measures could create a precedent over Iran. As the Venezuela decision loomed earlier in the month, Reuters suggested the US was looking to replace hidden oil trade, a response to sanctions, with transparent transactions. But at the same time, Venezuela pumping more oil could reduce pressure on Biden to compromise with Iran.