Grassroots Group Chipping Away At Iran’s Network In Canada

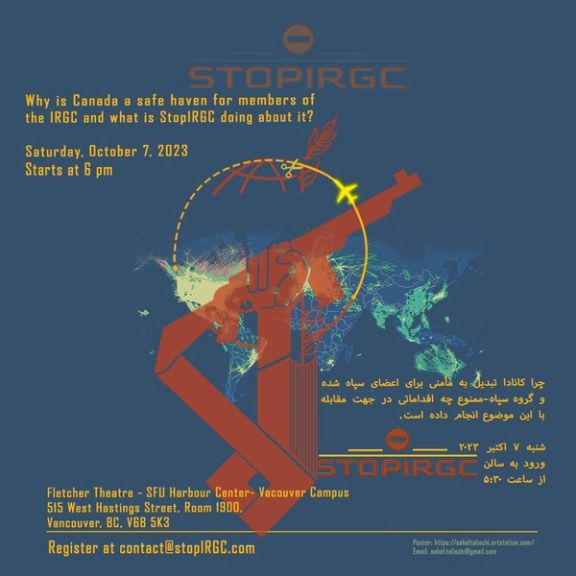

A grassroots group of lawyers and concerned Iranians in Canada is working to disrupt Iranian government influence operations in the country with the community’s help.

A grassroots group of lawyers and concerned Iranians in Canada is working to disrupt Iranian government influence operations in the country with the community’s help.

StopIRGC’s efforts, however, are insufficient to shut the open path the clerical regime in Tehran has managed to build into Canada. The Canadian government must take action, Mojedeh Shahriari, a cofounding member, told Iran International.

Since the death of Mahsa Amini in the hands of morality police in Tehran in September 2022, the coalition of lawyers has been trying to do its part to track the Islamic Republic’s agents, who spy on anti-regime activists, intimidate participants at "Woman, Life, Freedom" demonstrations and engage in money laundering and sanctions evasion on Canadian soil.

Shahriari described the Islamic Republic’s network in Canada as “similar to an international drug cartel”. She warned that they are even more dangerous than common criminals as they also try to make inroads into political and cultural spheres by influencing Canadian politicians at municipal, provincial and federal levels, as well as rallying Muslims in favor of their objectives through regime-linked Islamic centers.

Ramin Joubin, another StopIRGC cofounder, told Iran International that the group is hot on the heels of regime-related activities through at least four mosques in Alberta, Ontario and British Columbia.

The voluntary group is dependent on public reports about related suspicious activities, submitted by the Iranian community in Canada. According to Shahriari, the group “keeps receiving tips”, which they fact-check and subsequently use as basis of reports they prepare to send to authorities such as the police as well as immigration or border security in Canada.

“The reports people send us keep coming and our work is wholly dependent on those. Sometime sent anonymously, they provide a clue for us to pursue the cases,” she added.

The StopIRGC initiative, which officially started on a zero budget in 2022, has been welcomed by Iranian Canadians, “who have shown willingness in tracking, helping to expel” regime agents, said Shahriari.

The group's co-founder expressed satisfaction with law enforcement agencies such as the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), which has been "relatively cooperative" with StopIRGC and has shown interest in their work. However, she criticized the government of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau for not providing sufficient support to a group dedicated to raising awareness about "this serious security issue" in Canada.

“There is no indication of the Canadian government’s resolve to even address this security threat,” Shahriari said. “I hope at least they raise RCMP’s budget so they can investigate Iranian spies in Canada, whether with our help or independently.”

Taking suspected individuals to court is specifically challenging due to privacy laws in Canada and the fact that many of them are already Canadian citizens, Joubin said.

“More than 50 percent of those we are investigating are already Canadian citizens, which makes pursuing the matter more challenging,” he said.

Shahriari also asserted that those suspected of working for the Iranian regime are “more daring than you would expect as their pockets are full of money,” which emboldens them when it comes to legal cases such as the ones StopIRGC is pursuing.

One relevant case being independently pursued by a lawyer associated with StopIRGC involves the defendant using intimidation tactics against the plaintiff, who is now a Canadian citizen living in the US, in an attempt to halt legal proceedings.

The ongoing legal case in Calgary initially revolved around the defaulting of an 18-bitcoin debt borrowed by an Iranian owner of an exchange shop in Canada. However, as the plaintiff and their lawyer delved deeper into the matter in their pursuit to recover the money, they started uncovering what they allege to be a money laundering operation with connections to the Iranian regime. The plaintiff shared these details with Iran International on the condition of anonymity.

The defendant, whose father used to work in the oil sector during former President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s government, is just a benchman in a group of more powerful people allegedly working for the regime, the plaintiff believes.

Joubin, who is aware of some details of the case, said there are serious accusations of money laundering, sanctions evasion, and intimidation and that the defendant has filed for bankruptcy, a claim that Canadian authorities have already debunked.

The case is an instance of many other civil, defamation, criminal, and even family cases StopIRGC is looking into. The group is planning to release more details about their work this month.

StopIRGC cofounders asserted that following up on such legal procedures is a lengthy process, particularly when it comes to the more immediate dangers the regime’s network poses, such as infiltration into Iranian dissident factions in Canada.

Despite all the efforts in its one-year history, StopIRGC has not yet managed to help expel any regime agents, yet the members hope that their increasingly growing database would some day pave the way in abolishing the Islamic Republic’s foreign interference in Canada.

The group is already investigating multiple people suspected of working for Iran’s regime, who have shown up at protests to intimidate protesters and gather intelligence on the crowd, which is a common practice by the Islamic Republic, and well known by the Iranian diaspora across the world.

“There is this one case I’m investigating about a suspected person who showed up at an anti-regime protest in Vancouver and even spoke to the crowd in the guise of a dissident,” Shahriari said, stressing that these agents know how to dress and behave not to be mistaken as regime sympathizers.

According to the cofounders, the dissidents are intimidated via a series of tactics including stalking, trespassing into their properties and sometimes direct physical assault. The scale and scope of such threats are not only limited to Canada as the dissidents’ relatives are targeted inside Iran to exert pressure on them.

The threats posed by Iran’s regime might not seem immediate, Shahriari said, but the Islamic Republic and the IRGC are “a terrorist threat to the whole world and their presence here is guaranteed to cause serious troubles in Canada sooner or later”.

Some Canadian politicians have already made efforts to proscribe the IRGC, including in the Senate following numerous calls by Iranian activists, warning about the dangers they pose to Canadians.

In July 2022, Trudeau said Canada has designated IRGC leadership in response to crackdown on popular protests in Iran, yet activists have been signaling that the measure is insufficient.

While StopIRGC remains influential in lessening the risks and raising awareness about the issue, it does not have the means to deal with all the agents “who keep arriving in Canada”, Shahriari said, voicing hope that the next government would finally take on the task of proscribing the Guards as a terrorist entity.

Pierre Poilievre, the leader of Canada’s Conservative Party, running to be the next prime minister, vowed in late August to “kick out” IRGC if he wins office.

“If IRGC is listed as a terrorist organization, police will be obliged to take them on, and they will be tried as members of a terror organization. That should be the main effort,” Shahriari said, adding, “Meanwhile, all we can do is to investigate them further and continue to put pressure on the Trudeau government to take action against the IRGC and other Islamic Republic's agents in Canada.”