Western Sanctions Against Iran: Words Still Louder Than Actions

The new EU-US coordinated sanctions against Iran in the aftermath of Iran-Israel April 13-19 conflict is a notable development whose efficacious enforcement remains as elusive as ever.

The new EU-US coordinated sanctions against Iran in the aftermath of Iran-Israel April 13-19 conflict is a notable development whose efficacious enforcement remains as elusive as ever.

It took the Islamic Republic of Iran until the early hours of April 13 to respond to Israel’s April 1 air strike that eliminated 7 of its top brass in Damascus. Although the Iranian regime’s supposed “retaliatory” response that thrust over 300 drones and missiles from its soil directly unto Israel was in effect suspenseful affair with underwhelming physical impact, it has been foreboding of immense foreseen and unforeseen consequences. The rapid succession of EU-NATO leadership condemnations in the wake of the Iranian retaliation was the acknowledgement the potential destruction the Iranian strike could have wrought; had it not been successfully offset by a de facto entente of British, American, French, Israeli, Jordanian, and Saudi Arabian air defenses and air forces.

It was upon the comprehension of this reality that came the EU’s April 17, 2024 new sanctions against the drone manufacturing sector of the Iranian regime’s military-industrial complex. Promptly thereafter, Canada, UK, and US followed upon the EU sanctions with coordinated and correspondingly targeted identical suite of sanctions.

However, the question is, first, how these new sanctions figure in the greater scheme of sanctions that have already been set in place by EU, US, and their G7 allies against Iran. And second, whether there exist measures that can tangibly enforce them.

The Many Different Types of Sanction Regimes

Over the past thirty years, major world powers, particularly US and EU, have increasingly resorted to sanctions as a major “non-military” leverage against “adversaries” or states that are held in violation of international conventions and treaties. The US sanctions are the broadest and oldest anti-Iran sanctions ever devised dating back to the 1979 US embassy hostage crisis. After the US, EU countries have the second largest sanction regime. The EU’s sanction regimes against Iran have never been as consistent as the US ones due the many ups and down in EU-Iran relations. The third regime of sanctions are those of UK and Canada sanctions, along with those of Australia, Japan, and South Korea.

EU-US Standoff and Collaboration over Iran Sanctions

The US boasts the broadest sanction regime in the world that encompasses over 26 countries and ten thematic sanction regimes, from counter narcotic and nuclear non-proliferation to cyber crimes and Global Magnitsky sanctions. Hence, as the EU has often sought to cajole a regime like that of Iran’s, it should come as no surprise that the EU-US have often clashed as to the path forward and disagreed over sanctions over many other aspects of their diplomacy vis-à-vis Iran.

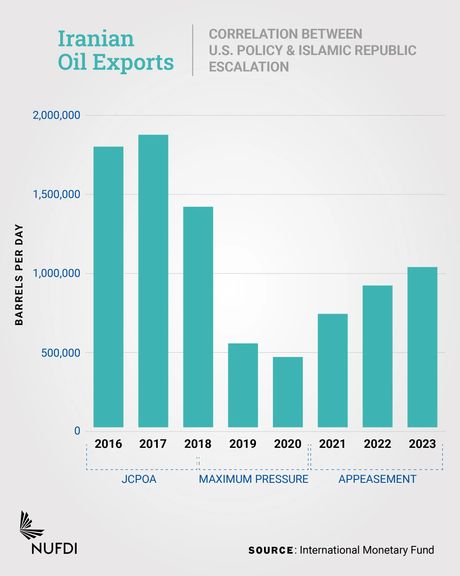

A bone of contention over sanctions between EU and US arose in 2018 when President Trump abruptly left JCPOA, aka, Iran Nuclear Deal, and brought forth the “Maximum Pressure” sanctions upon Iran by 2019. To EU’s chagrin, the entirety of US sanction regime included secondary sanctions that forced many EU enterprises to “wind down” their ties with Iran. EU’s historically “complicated” relations with Iran made it to part ways with the US on this occasion, which caused much tension in the EU-US relations during the Trump presidency. In fact, the EU chief mandarins sought to introduce swift measures to shield EU enterprises from the wrath of US secondary sanctions.

Nonetheless, the Iranian regime’s mass repression of popular protests in 2018 and 2019 culminated to the statewide crackdown of 2022 Woman, Life, Freedom uprising, and forced the EU to adopt up to ten packages of human rights-based sanctions against various Iranian regime individuals and entities between 2018 and 2023. It was at this juncture that the EU’s resistance in joining the US comprehensive sanctions against Iran began to erode.

As the Tehran regime became a major supplier of drones and missiles to Russia in the Russia-Ukraine war, the EU became host to millions of Ukrainian refugees. Alarmed by Tehran’s increasingly supporting role for Russia’s war effort, the EU introduced the first set of sanctions against the Iranian missile and drone manufacturing in 2023.

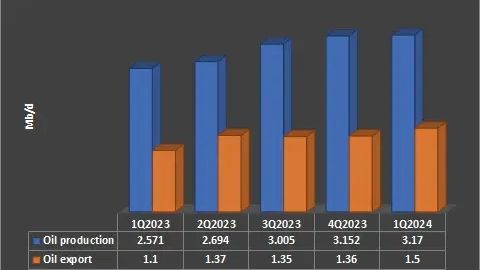

It should be highlighted that although the Biden administration maintained the Trump-era sanctions on Iran’s oil exports as it was negotiating a revival of the JCPOA, enforcement became a secondary concern since January 2021. This allowed Iran to more than double its oil exports to China by 2023 and weaken the sanctions regime.

With the escalation of the conflict in the Middle East post-October-7, the Iranian government continued to supply both its proxies in the region and Russia further afield with projectiles of various kinds becoming a brazen global arms supplier undeterred by any measure of sanctions. The EU looked on warily and Josep Borrell, EU foreign policy chief, struggled to avoid slapping sanctions upon it but to no avail. The last episode that consolidated EU-US collaboration on coordinated sanctions against the Iranian drone and ballistic manufacturing was the Iran-Israel conflict of 7-13 April 2024.

Sanctions: Enforcement and Effectiveness

Whether or not the US and EU would exert the will to enforce the sanctions remains the sticking question. In the last package of sanctions, including the Mahsa Act, passed by the Congress and signed by President Biden, there indeed exist many a set of measures to stop the Iranian petroleum exports, which constitute a major source of revenue for the Tehran and its military-industrial complex.

However, many experts have cast doubt unto whether Biden administration would be willing enforce them in this election year. Evidently, administration fears such a rigid enforcement may cause the price of oil to skyrocket globally and may thus refrain from the enforcement of such sanctions. Whereas Biden administration is loath to enforce the oil sanctions on Iran, the US Treasury is seeking new authorizations to counter the Iranian regime’s abuse of bitcoin and the dark web to circumvent sanctions.

Such contradictions have been Biden’s foreign have not gone unnoticed and the mullahs in Tehran have certainly tried to take advantage of it. Over the past several years, both Iran and Russia have shown much dexterity in circumventing sanctions, from dark web and bitcoin to shadow commercial fleets and overland routes. Prescient studies reveal that Iran’s shadow fleet of tankers ship oil to Malaysia which gets rebranded as Malaysian oil and then exported in China. Absence of appropriate sanction enforcement measures have similarly enabled Iran to smuggle arms to the Hezbollah of Lebanon using EU ports.

Enforcing so many sanctions targeting so many countries is no small feat. It requires much investment in digital and physical infrastructure as well as human resources. Neither the US nor the EU appear to be fully equipped with the requisite tools and human resources to enforce their ever-expanding sanction regimes; especially, vis-à-vis Iran. Since February 2024, the Biden administration is yet to appoint a permanent official to oversee the enforcement of the ballooning sanctions against Iran at the US Treasury. As to the EU, the problem of sanction enforcement has been even more complicated. Still, not until after several consultation rounds between the EU Council and the EU Parliament did the latter finally manage to pass rules that crack down on member state’s failure to enforce EU sanctions on March 12 of this year, whilst the broadest set of EU wide sanction against Russia dates back to February 2022!

Today, sanctions have become a permanent fixture in the global foreign policy and international trade establishment. A growing literature is focusing on sanctions and their effectiveness. Amongst the many works that have been published on the topic, there exist ostensibly academic volumes such as How Sanctions Work: Iran and the Impact of Economic Warfare(Bajoghli, Nasr, et al, Stanford University Press, 2024). Such “studies” illustriously correspond in authorship and stance to those of “Iran Influence Network”, and it is thus no wonder that authors of such works are increasingly forced to tread a fine line between lobbying and consultancy. Other stakeholders concerned with the growing sanction regimes are globally active enterprises who have built comprehensive databases that catalogue “risky individuals and entities” to help them in compliance with the global sanction regimes. Such works may be a good starting point to verify governments’ commitment to sanction enforcement.

In the end, if the EU and US fail to substantially implement the many sanction regimes that they have created over the past several years, they may lose much in prestige in credibility in the eyes of the world community where Russia and China have been jockeying to replace them as global powers. The last curtain in this segment is yet to draw.