Two years after the attack: Salman Rushdie, the fatwa, and resilience

On August 12, 2022, Salman Rushdie, an Indian-born British-American novelist, was viciously attacked as he prepared to speak at the Chautauqua Institution in New York.

On August 12, 2022, Salman Rushdie, an Indian-born British-American novelist, was viciously attacked as he prepared to speak at the Chautauqua Institution in New York.

The assailant, armed with a knife, rushed the stage and stabbed the renowned author multiple times, inflicting severe injuries. Rushdie, who had spent decades living under the shadow of a fatwa calling for his death, was once again fighting for his life. This brutal incident, occurring more than three decades after the initial controversy over his book “The Satanic Verses,” starkly reminded the world of the enduring dangers faced by those who dare to challenge religious and political orthodoxy.

The Satanic Verses was published in September 1988. Rushdie's magical realism novel explored themes of religious faith and identity and was met with immediate outrage from many in the Muslim community. Protests began in October 1988 in the United Kingdom and quickly spread across the globe. The book was condemned as blasphemous, leading to its banning in several countries.

By October 1988, the book had been banned in India, and by the end of the year, it was also banned in countries like Bangladesh, Sudan, South Africa, and Sri Lanka. Protests intensified, with public book burnings in the UK, including a high-profile incident in Bradford in January 1989.

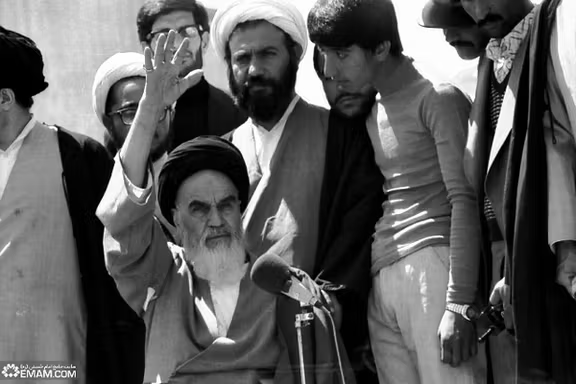

The situation escalated dramatically on February 14, 1989, when Ruhollah Khomeini, the Supreme Leader of Iran, issued a fatwa calling for Rushdie's execution, along with anyone involved in the publication of the novel.

The fatwa posed a personal threat to Rushdie and represented a broader challenge to the principles of free expression. Rushdie was forced into hiding, living under police protection for years. The fatwa led to violence and fear, with translators and publishers associated with the book being attacked, and even killed, in some instances. The global response was mixed; while many condemned the fatwa as an attack on free speech, others supported the outcry against what they saw as an insult to Islam.

The issuance of the fatwa against Rushdie came on the heels of another atrocity orchestrated by Khomeini—the mass execution of over 5,000 Iranian political prisoners in the summer of 1988. These prisoners, many of whom had already served their sentences, were summarily executed following brief, sham trials. The international community largely remained silent, failing to condemn this gross violation of human rights. This silence likely emboldened Khomeini and his regime, leading them to believe they could similarly impose their will through the fatwa without significant global repercussions. Just as they had stifled dissent and eliminated opposition within Iran, they sought to extend their reach by suppressing freedom of speech beyond their borders.

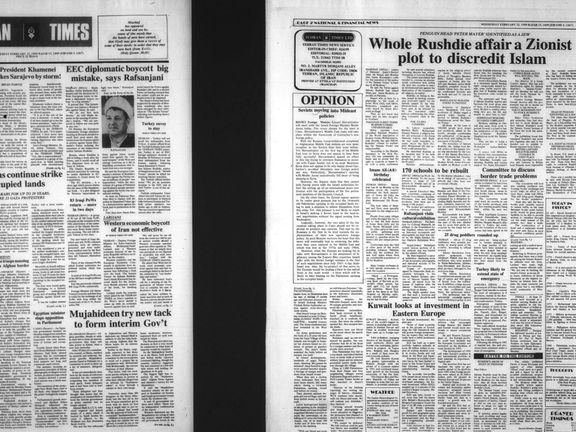

The Tehran Times, a prominent English-language Iranian government newspaper, is closely linked to the Islamic Development Organization, a religious and cultural entity created by Khomeini in 1982 to promote the ideologies of the Islamic regime. During the controversy surrounding Rushdie, the Tehran Times played a pivotal role in spreading the regime's propaganda and fueling global outrage, particularly in advancing the Islamic Republic's objectives abroad.

The Tehran Times became a mouthpiece for the regime, fervently defending the fatwa and condemning Rushdie in line with the directives of the Islamic Republic, echoing its stance on religious and political issues. Its editorial board penned and oversaw numerous opinion pieces defending the fatwa and condemning Rushdie. The newspaper, reflecting the regime's stance, framed the entire affair as a "Zionist plot" aimed at discrediting Islam. One headline read, "Penguin head ‘Peter Mayer’ identified as a Jew. Whole Rushdie affair a Zionist plot to discredit Islam."

Following this, the Tehran Times editorial board published an opinion piece on March 7, 1989, arguing that Britain should ban the book, citing previous cases like Spycatcher, where books had been banned for much less: "If Spycatcher can be banned and condemned, then why not The Satanic Verses, which has hurt 1 billion Muslims and others who believe that the beliefs of others should be respected."

Statements from other Iranian leaders further reinforced the fatwa. Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, then Speaker of the Iranian Parliament, declared that "only burning Rushdie’s book will diffuse the crisis." Tehran Times headlines echoed this sentiment, with proclamations like "Rushdie not forgiven, even if he repents" and "Rushdie is a dead author." The rhetoric was intense, with the Tehran Times reporting on the "rare solidarity" among Muslims worldwide and the increasing death toll in protests, such as the one in Bombay where 12 people were killed.

Despite the passage of time, the fatwa was never officially rescinded, and the threat to Rushdie's life remained. The attack in 2022 underscored that, even after decades, the tensions sparked by The Satanic Verses had not fully abated. The IRI’s hope of riding the wave of religious fervor backfired in the long term, as the protests eventually subsided, and the geopolitical costs became clear. The IRI had overestimated its influence, as demonstrated by headlines such as "European Economic Community (EEC), stand on Rushdie affair not to their interest" and "West losing over its defense of Satanic Verses," both of which reflected the regime’s frustration with the West's steadfast defense of free speech.

If Britain and other European countries had given in to Tehran’s threats, we would be living in a vastly different world today—a world less free, less tolerant, and more fearful. These nations' firm refusal to ban the book and defense of free speech upheld fundamental human rights. It prevented a dangerous precedent where violence and intimidation could dictate the limits of expression. Their refusal to capitulate preserved the principles of liberty and ensured that the forces of censorship and extremism would not easily silence dissenting voices.

Salman Rushdie's resilience in the face of sustained threats has been remarkable. His most recent work, Knife, published after the attack, is a testament to his unyielding spirit. The book explores themes of survival and the power of storytelling, offering a message of hope and defiance. Despite the physical and emotional scars left by the attack, Rushdie's commitment to his craft and the ideals of free expression has not wavered. Knife is more than just another novel; it is a declaration that neither the fatwa nor the violence it inspired can silence Rushdie's voice. Its hopeful message resonates deeply, especially in a world where the threats to freedom of speech continue to evolve.

Reflecting on the attack and the legacy of the fatwa, it's crucial to recognize the broader implications of Rushdie's experience. His story is not just about one man or one book; it represents the ongoing struggle for the right to speak freely, to question, and to create. The endurance of Rushdie's voice, despite numerous attempts to silence it, inspires all who believe in the power of literature and the necessity of defending freedom of expression. The attack on Rushdie in 2022 was a tragic reminder of the enduring dangers he faces, yet it also highlighted the strength of his resolve and the lasting impact of his work. His journey, marked by immense challenges and extraordinary resilience, continues to be a beacon of hope for those who value the freedom to express ideas, no matter how controversial.